Book Review Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England: A Study in International Trade and Economic Development. By JOSEPH E. INIKORI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. 576 p.

Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England written and published in 2002 by Joseph Inikori is certainly one of the major contributions on the role of Africans and international trade in England’s industrialization and long run economic development. Joseph Inikori is an Anglo-Nigerian historian currently professor in the university of Rochester and conducting research in Atlantic World Economic History. He has published several articles on Atlantic slave trade and its impact on England economic development, the culmination of his work and research being Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England which received the Association of African Studies Best Book Prize in 2003, one year after publication. This illustrates the importance of Inikori’s book for African scholars and researchers who are eager to demonstrate the historical importance of Africa and slavery of Africans in the rise of Western Europe (but mostly here England) modernity, economic supremacy and development.

The present book has hence established itself as a reference and magnus opus on the causal links between African slavery and the Industrial Revolution in England in the 18th century. It is interesting to note that there are only few economic history books which stress with so much focus and insistence on this causal link between African slaves, Atlantic trade and Industrial Revolution. As Inikori argues in his book, the only major contribution on that matter before him was Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery (1944) which explained that slave trade and production directly contributed to the Industrial Revolution thanks to huge amounts of profits made by British merchants and slavers who then re-invested in the productive sectors which were the basis of the Industrial Revolution. In other words, the accumulation of capital made through African slavery allowed for England’s industrial financial investment at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. However, Williams’ profit-based argument was heavily criticized, the main critics being about the final use of those slavery-based profits (were they really invested in the Industrial Revolution?); the fact that Britain industrialization required no so much profits and that the funds mainly came from England’s own domestic resources. Inikori is aware of those matters and argues that Williams’ thesis is not so well suited anymore to explain England’s industrialization. He also tries to explain Williams’ focus on profits because of the influence of Keynesianism (in which profits play a great role for investments and growth and Williams wrote and published in the Keynesian Era) but adds that Keynesian theory is valid for already well-developed economies and not so much for pre-industrial England (p. 5-6).

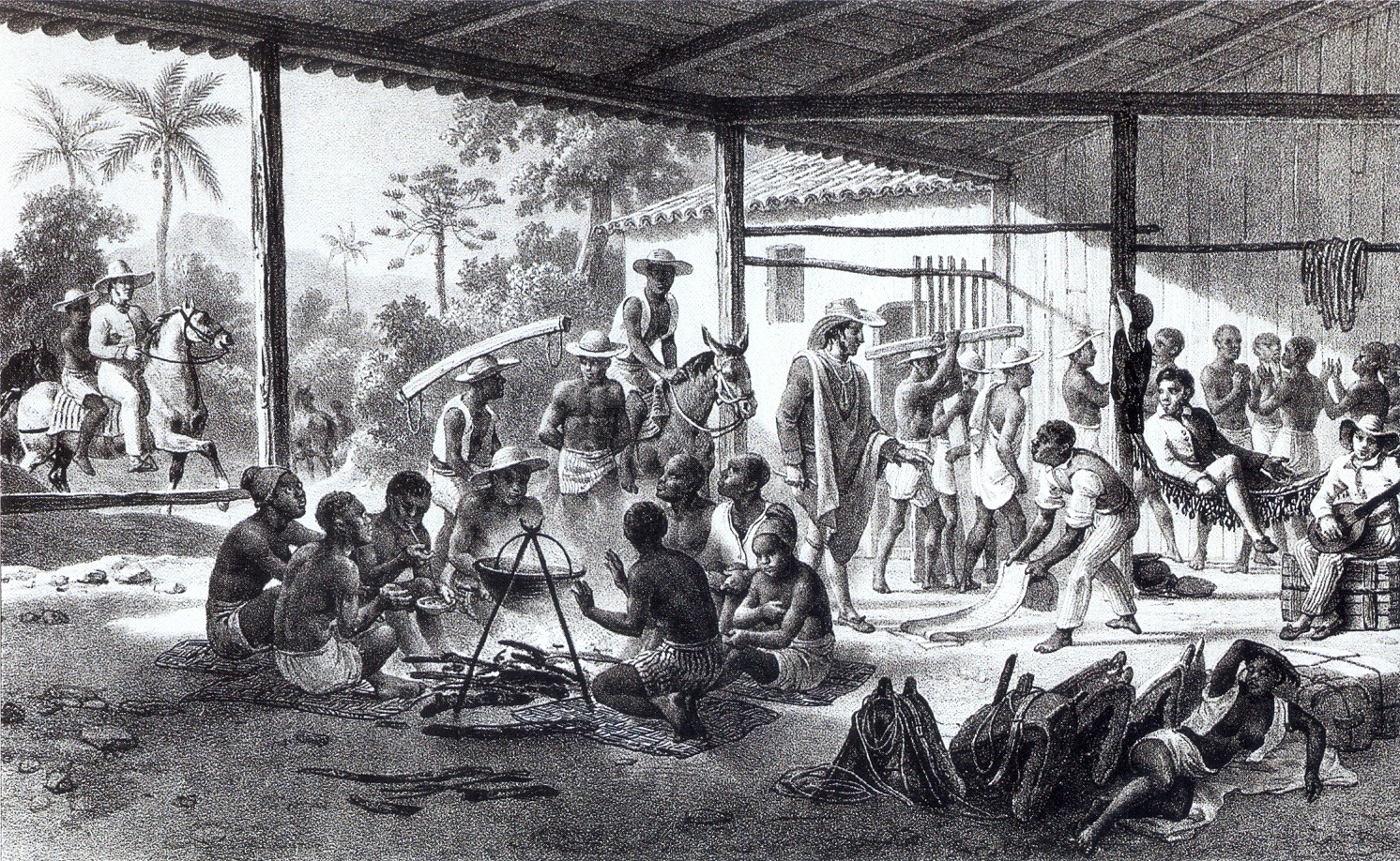

One could thus consider Inikori’s book as an attempt to go beyond Williams’ argument and “modernize” the explanations of the links between African slavery, Atlantic commerce and England’s development. To reach this goal, Inikori is heavily influenced by development economics’ conceptual framework. He draws inspirations and insights from prominent development economists such as Albert Otto Hirschman (1915-2012) and Hollis Chenery (1918-1994). The main contribution Inikori draws from development economics is the famous industrialization through import substitution model (ISI), for he argues that Industrial Revolution in England was “the first successful case of import substitution industrialization” (p.10). But what are the links between ISI, African slavery, Atlantic international trade and the Industrial Revolution? Inikori has to prove two mechanisms to support his thesis on the causal links between enslavement and exploitation of Africans, the rise of Atlantic commerce and the Industrial Revolution in England. The first mechanism is the causal link between Atlantic commerce and England’s Industrial Revolution (the former causing the latter). The second is the fact that growing Atlantic international trade and commerce were based on African slave labor in the Americas. We will see that the second mechanism is rather obvious and easily proved and that the first one is the main contentious part of the argument.

Inikori argues that during the Middle Ages onwards (roughly 1086-1660 which is the focus of chapter 2) England developed progressively, from 1086 to 1300 and then from 1475 to 1660, an economy specialized in woolen textile industry and that this industry was mostly export led. This specialization in woolen textile manufactures was England’s first successful ISI accomplished in the 16th century and, along with steady improvements in agriculture, made South England relatively rich. Thus, from 1086 to 1660 England moved from agricultural subsistence production to production for market exchange (p.43). However, market demand reached a limit and England could develop its industry further only through new expanding market demand. Inikori makes an important difference between two types of ISIs: both consist in an economy initially producing primary goods for export which then tries to substitute its imports by import-replacing manufactures thanks to state policies (fist for consumer goods, then for intermediate and capital goods). The distinction between the two models is that the first rely exclusively on internal autonomous forces and the second starts to open at some point to international trade and manufactured exports take a central place. All of Inikori’s argument is to show that England’s success corresponds to the second model (p. 150).

New markets for British products were thus found thanks to Atlantic trade and commerce (America’s and Africa’s market demand) which were based on Africans slave labor. After constructing an impressive navy and establishing military dominance in Atlantic Sea in the late 16th century (for example after defeating the Invincible Armada in 1588) and therefore acquiring colonies in America, England obtained access to huge market outlets. However, Inikori does not elaborate further on England’s military dominance of Atlantic Sea and this decisive factor lacks an explanation in the author’s work: why was England in the end militarily superior to the Spanish or the Dutch? The book does not provide a precise answer and Inikori only focuses on shipping in chapter 6 to argue that England’s growing shipping industry was stimulated by rising demand for ships due to overseas trade.

Regardless, it was the access to new markets in Africa and in America’s colonies which enabled England to further its industrialization through import substitution strategies. Imports of cotton textile from India, for instance, gave impetus to local English entrepreneurs to try to venture into cotton textile manufacturing. Protectionist policies, access to outlets in British American colonies and Africa and raw cotton provided by American colonies where production in plantations were based on Africans slaves labor permitted England to successfully achieve import substitution in the cotton industry which is recognized as one of the most crucial sectors of the Industrial Revolution. The reader could be surprised of the relatively few pages focusing on cotton industry in chapter 9 (about 20 pages: pp.427-451) since the Industrial Revolution mostly began with the cotton industry and its technological improvements, but Inikori is right when he argues that this industry developed under the impetus of access to overseas African and American markets and based on raw cotton provided by slave labor in British American colonies. Nonetheless, I think we could also consider the possibility of counterfactual although it may sound speculative: could have England developed its revolutionary cotton industry without African slave labor? This question is a matter of substitutability degree of labor and imports: one could argue that the specialization of Egypt in raw cotton production in the middle of the 19th shows that imports of raw cotton was perhaps more flexible than what Inikori seems to consider.

Regardless, Inikori’s methodological work is impressive: it offers vast amounts of quantitative data in table form as well as qualitative data through archival researches of a great varieties of historical reports and records. His quantitative and qualitative archival research and evidence allow the author to provide critical reviews of the existing literature on the subject and even to re-evaluate some estimations for example in chapter 5 in which he discusses the measurement of the importance of slave trading between 1600-1850. However, Inikori’s data analysis seems sometimes futile and can blur his main argument as well as confusing and overwhelming the reader. For instance, the author spends pages of digression discussing in vain population and GDP estimates of Domesday England in chapter 2 or Africa and America population estimates before Atlantic trade’s emergence in chapter 4.

Perhaps the book’s boldest argument and examination to prove the link between Atlantic trade and England’s Industrial Revolution lies in its regional analysis of pre-industrial England. In fact, the regions which started the Industrial Revolution: Lancashire, Yorkshire and the West Midlands (but mostly Lancashire), were the poorest regions of England at the time with relatively low population, low wages and poor overall wealth. As soon as those regions connected to overseas markets, industry, wages and population grew. Inikori carefully shows that population growth was autonomous in those regions (no migration from agriculturally productive and wealthy South regions), that industry growth was not led by internal demand since there was no national market yet until railroads construction in the 19th century and finally that technological innovations took place in those regions and were thus stimulated by high overseas demand. The only reason left to explain North West England industrial growth is thus the access to overseas markets in America and Africa. This is the central argument of the book and I think the most important, since proving that Atlantic trade was based on Africans’ slave labor is rather indisputable, obvious and largely admitted in the literature.

In the end, Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England definitely shows that African slave labor significantly contributed to England’s Industrial Revolution. Notwithstanding, its precise form of contribution, whether it was the decisive and unique causal factor or a factor among many remains a contentious matter. Inikori seems to consider that it was the decisive and unique factor, taking thus, in my opinion, an excessive straightforward position. Economic history phenomenon can rarely be explained through unique factors and when one focuses too much on one possible factor, other important causes can easily be overlooked. Other research exploring the role of colonization of America by England in the Industrial Revolution without taking such exaggerated straightforward perspective can be found for example in Pomeranz’ Great Divergence (2000) which combines multiple factors such as access to overseas markets and lands through colonization of North America (joining thus partly Inikori’s argument) and access to coal to explain England’s Industrial Revolution and which is, I think, a good complement to Inikori’s work. I also believe that Inikori attributes excessive importance on Atlantic trade, discounting the important role of trade with India and China which were also crucial (as we saw, cotton textiles imported by the English East India Company which stimulated ISI strategy in this sector came from India and another example is China’s demand for silver which made America’s silver mines profitable for decades).