Crises & cycles

One of the most striking phenomena in capitalist mode of production is certainly the recurring and systematic outbreak of financial and economic crises. Since the emergence of capitalism as a mode production in England during the 18th century and its progressive spread in Europe in the 19th and then in the world in the 20th and 21th centuries, the economy of capitalist countries must endure what economists call “business cycles”, that is to say, cyclical appearances of economic booms in production, employment and prices and busts (decline in production, employment and prices).

However, the acknowledgement of business cycles as such took a long and tedious path. The first main broad examination of economic crisis can be found at the beginning of the 19th century during the famous “General Glut Controversy” which involved famous economists such as Say, Ricardo and Malthus. Say, for example, argued that long-term deep economic crisis could not occur because of what will be afterwards called “Say’s law”, that is, the fact that there can be no overall overproduction crisis since production creates its own demand. It creates its own demand mainly because it generates products which can be directly exchanged for other ones. For example, If I produce coffee beans and sell it, all the value I got through selling will be in return my demand for other commodities by the same amount of value. Marx, who can be considered as a pioneer in crisis and business cycles theory, made his critic of Say’s law a point of departure of his bold thoughts on crisis.

Marxists theories of crisis

As Foley’ Understanding Capital (chapter 9) argues, there is no precise, consistent and modelled theory of crisis in Marx’ writings. In fact, he had diverse and dispersed analysis of different types of economic crisis that Marxists reconstructed and developed afterwards. Nonetheless, Marx’ main point on crisis is the following paradox he underlined: the capitalist system is characterized by an abundance of products (use values) due to tremendous developed productive forces and, at the same time, unfulfilled desires on the part of the working class. According to Marx, the main reason lies in the fact that production is carried under capitalism not to fulfill needs (produce use-value to satisfy needs and desires), but to accumulate profits (or, in Marxist terms, surplus value). Marxists reconstructed then three main theories of crisis: disproportionality crisis, underconsumption crisis and crisis due to the falling rate of profit.

Firstly, in Capital Volume 2, Marx sets up a model of capital circulation through two department: department I (production of means of production) and II (production of means of consumption). For those two sectors to have balanced growth, there should be a balanced investment level between the two, such that there can be no overproduction in one department and/or not a lack of production in the other. The problem is that it is rarely the case, since capitalist allocate their capital not in order to balance the two department, but to accumulate surplus value. This type of crisis is called “disproportionality crisis”.

Secondly, the underconsumption theory underlines the striking feature of the inability, under capitalism, to sell all the produced commodities. Since workers only receive a part of the value they produce in the form of wages, aggregate demand has a tendency to be always lower than the supply. Hence, their purchasing power will always be lower than the value of the produced commodities which need to be absorbed. This leaves an excess supply in the market and crisis follows. Foley argues that this version of the underconsumption theory is simplistic, because that part of the value that the worker does not get goes as income to the capitalist, who can also support additional demand for output (through consumption, or through investment, a point whom which Marx was aware of). At this precise point, Rosa Luxemburg had an important and rather unorthodox analysis. She argued that capitalist economy is structurally incapable of generating enough aggregate demand. Her argument is that even if capitalists have enough money and the willingness to invest (which would normally support aggregate demand), they cannot invest ad infinitum. In effect, the purpose of investment is in fine also to produce consumption goods (it is also its justification), one cannot invest only to accumulate means of production per se. Foley underlines the fact that this analysis by Luxemburg is strikingly un-Marxist, since Marx himself argued that the ultimate goal of capitalist production is accumulation of surplus value.

Thirdly Foley explains two versions of the falling rate of profit theory, the first being the “profit squeeze” theory and the second the tendency of falling profit rate: 1) The expansion phase of the business cycle leads to higher employment, the workers’ bargaining power rises and thus wages rise. That leads to a fall of the profit rate and this leads to a crisis since capitalists do not invest further until production and employment fall enough to decrease workers’ bargaining power so that wages decrease and profit rate can go up. 2) Pressured by competition and the search for profit to innovate, the capitalists tend to replace more and more labor by capital, that is, mainly machinery and equipment goods. In Marxist terms, there is a rise of the organic composition of capital (c/v with c=constant capital: machinery, equipment; and v the variable capital: wages) which leads to a fall of the profit rate (defined as p=s/(c+v) = (s/v)/(c/v+1) with s the surplus value).

From crises to Business cycles

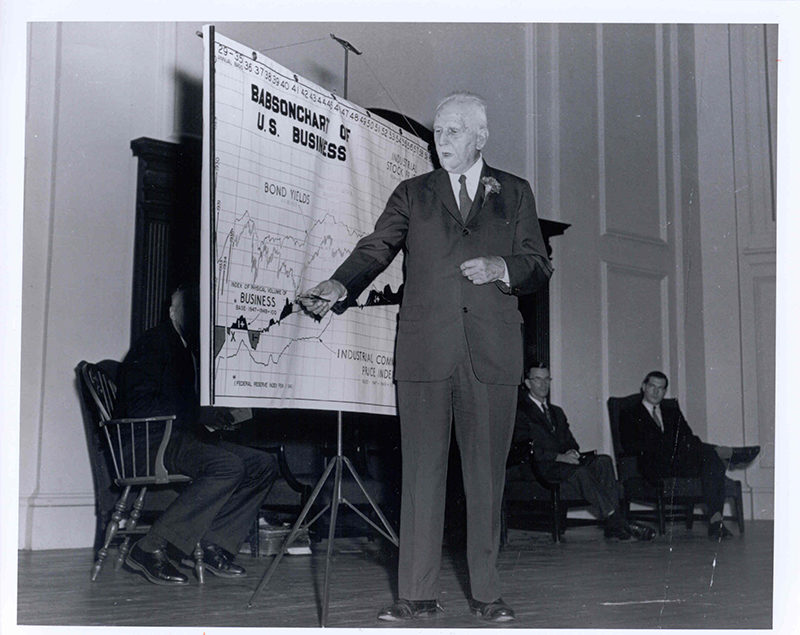

Apart from Marx and Marxists scholars, another trend emerged in the end of the 19th and in the first half the of 20th century: economists who became increasingly interested in the measurement and analysis of business cycles. The biggest impetus in that matter can surely be accredited to Wesley Clair Mitchell (1874-1948) who was the first director of the National Bureau of Economic Research (founded in 1920) and conducted tremendous research on the measurement and analysis of business cycles. Influenced by Thorstein Veblen and his critic of neoclassical economics, Mitchell sought a new way of conducting economic analysis and research, mainly through historical and empirical data analysis. He was convinced that his empirical and inductive approach (constructing new theories from empirical evidence) would make older economic theories obsolete: “quantitative analysis” would produce more robust economic reasonings than “qualitative analysis”, that is, neoclassical deductive approach. Conclusions Mitchell drew from his work are remarkably similar to Marx’: business cycles are chiefly driven by the incessant pursuit for profit. Assuredly, Mitchell’s work paved the way to a golden age of statistical and quantitative analysis of business cycles in the 1920s, so much that even economists hitherto not interested in that domain sought to bring their own contribution to business cycle analysis. A striking example is surely Irving Fisher (1867-1947) and his debt-deflation theory. Fisher, who recognized that he was a newcomer on the subject, made a distinction between “forced cycles”, cycles determined and driven by external factors (Fisher gives the example of the sun spot theory which sought to explain economic cycles through astronomical cycles) and “free cycles”, namely, cycles whose prime movers are not external, but inherent and intrinsic to the cycle. It is to this latter case, the free cycles, that Fisher wants to explain taking what he calls a “economic science” point of departure as opposed to economic history which only describe business cycles. Fisher wants to identify relations and tendencies that drive the cycles. His main idea is that the main two factors are (1) over-indebtedness and (2) deflation, the former being more important than the latter. The state of over-indebtedness leads to worries on the part of either debtors and/or creditors. As debtors try to sell their assets to pay back their debts, the quantity of money in circulation and the velocity of money decline (agents consume less to save). This leads to a fall in price level and a paradoxical situation where the more economic agents try to get rid of their debts, the more its value in real terms rise: “the more the debtors pay, the more they owe” (Fisher 1933: 54). The fall in general price level leads to a fall of profit rate and hence to a decline of production and employment. This leads to general pessimism, loss of confidence and hoarding, the value of money rises even more, prices decline further and the real interest rate rises. Fisher argues it would be insane not to intervene through economic policy and that the economy should not be left to natural market forces: reflation policy becomes necessary. However, it would not be sufficient, since the main problem of the tendency towards over-indebtedness remains. This leads Fisher to explore some of the reasons which drive the economy towards this state of over-borrowing and over-indebtedness. He argues, finally, that the mains factors are the new investments opportunities associated with great profit expectations (because it will encourage agents to borrow to invest). Those new investments opportunities are, in return, created by new inventions and technological breakthrough and progress.

Conclusion

To sum up, analysis of business cycles began first with inquiries and reflections around market gluts and economic crises. As we saw, Marx and Marxists scholars can be considered as pioneers in the analysis of crises and business cycles. Outside Marxism, it was W.C. Mitchell who gave the greater impetus into business cycles analysis. As stated above, Mitchell and Marx analysis of business cycles as profit driven are similar. Nonetheless, I think Marx’ investigation goes one step further, as he also sought to explain the origins of profit through exploitation and the extraction of surplus value. Notwithstanding, Mitchell’s contribution improved greatly the quantitative measurement and analysis of business cycles in such a way that it even drew a mainstream neoclassical economist such as Irving Fisher to elaborate a bold economic theory regarding business cycles. However, if Fisher’s debt-deflation theory provides insights into the economic mechanisms of economic crises and cycles, it is limited by the fact that it neglects the political economy/ political aspects which have an important role in business cycles (one could also argue that Mitchell also omits this fact, as many business cycles economists did). In conclusion, I would like to acknowledge the important works of Kalecki, who, in that matter, successfully incorporated a political economy dimension into business cycle analysis, an analysis I find particularly valuable (this theory is briefly explained in Foley’s book chapter). In his political business cycle theory, Kalecki argues that cycles are characterized by shifting class alliances between the working class, the business class and the rentiers: during a crisis, the business class pressures the state to revive the economy, aligning thus its class interests with those of the working class. As production and employment rise thanks to state intervention, the business side becomes progressively more reluctant to it, because it loses bargaining power (jobs are secured and workers do not fear unemployment and sacks). As employment and inflation rise, the capitalists have incentive to pressure the state to conduct more orthodox economic policy: this puts an end to the expansion phase of the political business cycle until the economy slumbers once again in a crisis in which state intervention is once again required and so on and so forth. Foley argues that Kalecki’s political business cycle model is a recent underconsumptionist theory, because it stresses the incapacity/unwillingness of a capitalist-dominated society to tolerate a high level of aggregate demand for too long.